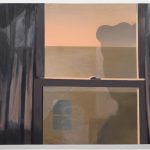

There are days in our lives that are big, lasting, life-changing. Then there are the days in between: filling out a spreadsheet at work, cleaning up empty beer cans as you prepare for the week ahead, the changing of light on the wall as the day grows long. These are the little moments in between the big momentous ones and they are the fascination and subject matter of Matt Bollinger’s creation, Between the Days.

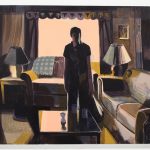

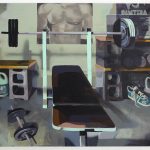

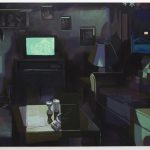

Between the Days was a solo exhibition at Zürcher Gallery in New York that included paintings, sculptures, and an animation. The works depict the Kansas City suburb where Bollinger grew up, in a modest ranch house not unlike the one which his characters Carolyn, a mother, and James, her grown son, pass through in a cycle of waking, watching, smoking, drinking, and working out.

In the animation, figures emerge from strokes of paint moving into forms and ultimately entire scenes. At times, it seems as if color and light are painting themselves into existence. When there is movement, often it is just the outline of the form that moves, the fill and shading left to catch up once the movement stops. The effect is almost that of a slow shutter motion blur photo. The viewer is left to wonder, what am I looking at, is this paint? Film? Something momentous? Or merely the moments between. That is the muted ambiguity of Between the Days.

Bollinger is a visual artist who works primarily in painting and drawing. “Over the past several years,” he told us, “I’ve begun animating my paintings so I can more directly flesh out the narratives I’ve been writing. It’s important to me that at the end of the process, I have both a film and physical paintings for exhibition.”

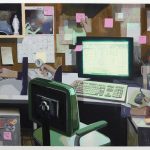

We asked him about the process of turning paintings into film. “The production began with me making many paintings in flashe (a vinyl paint) and acrylic at different sizes, from small (12″ x 16″) to large (60″ x 90″),” he said. “The small paintings all corresponded to a single camera angle. These I animated by first photographing the painting and then making a small change before shooting it again. The large paintings were different. Because they were so much bigger, I could shoot them both without cropping and in close up.”

The process itself informed the finished product because he used painter’s tape to mask the close ups. “Afterward,” he said, “when I removed the tape, the painting had a noticeable edge or interruption from the framing. While these didn’t show in the film, they created a subtle fracturing in the painting’s space after the fact. This distinction between the animation and the paintings was important to me when they were exhibited.”

When we asked how it was for someone who is primarily a painter to make the shift into picking up the technical gear involved in stop-motion and he said, “Dragonframe changed my process completely. Prior to this animation, I had worked without the aid of any application to capture my images. This meant setting up a shot and then animating without knowing how the footage looked. As a painter, I thought, I’ll keep the technological side as simple as possible. After the first time I shot for several hours without noticing my camera was out of focus, I was ready for better gear.

“I rely on Dragonframe’s live view to work out the timings for my animation—sometimes shooting in 1’s, 2’s, 3’s, or some combination based on how things are looking. Because making paintings can be a very organic process, it’s helpful to have onion skinning to keep an eye on how I’m pacing a movement. While working, I tend to have several brushes in hand, along with the keypad controller. I make marks, step out of frame, and shoot. We’ll see how long I make it before I need a new controller. This one is slowly getting covered with paint.”

Sounds like something we’d like to see! But until we can bring you that image, here are some other behind-the-scenes pics of Bollinger’s paint+animate journey: